Lately, I’ve been working on migrating Doctrine ORM to PHP 8 syntax. To that end, I’ve been using Rector, an automated refactoring tool. It comes with a set of rules called LevelSetList::UP_TO_PHP_81 which makes sure you use the most modern syntax to do something as long as it is supported on PHP 8.1. UP_TO_PHP_81 is equivalent to UP_TO_PHP_80 + PHP-8.1-specific rules. UP_TO_PHP_80 is equivalent to UP_TO_PHP_74 + PHP-8.0-specific rules. UP_TO_PHP_74 is equivalent to… you get the idea, and maybe also marvel at how satisfying this looks. 🤓

I’m doing that work on the 3.0.x branch because we don’t currently plan to drop support for PHP 7.1 on the 2.* branches. While I’m at it, I’m taking this as an opportunity to add type declarations where not already present.

Adding type declarations is very often a breaking change, especially when working on methods that are not private, and classes that are not final,which explains why that was not already done everywhere on lower branches.

Thankfully, we have plenty of phpdoc comments that Rector can use to infer the correct type declarations to add. Here is how such changes might look:

- /**

- * @param string $foo

- *

- * @return int

- */

- public function doStuff($foo);

+ public function doStuff(string $foo): int;doctrine/orm is a lot of code though, so I’m trying to work in bite-sized pull requests. First, because it would be awful to review all these changes at once, but also because the phpdoc we have can be imprecise, or plain wrong (we still have to work through our PHPStan and Psalm baselines). Having inaccurate phpdoc might be fine from PHPUnit‘s point of view, but having inaccurate type declarations isn’t, so I need to fix these by hand afterwards.

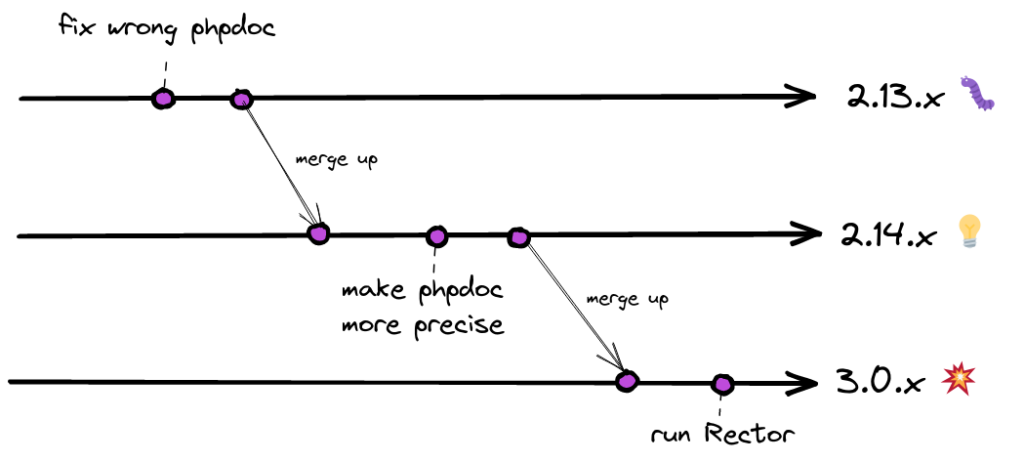

I like to repeat that we’ve never been closer to releasing doctrine/orm 3.0 than we are today, an information that you can share widely because it’s always true. While that’s a fact you can hardly deny, it is still good to backport any of the fixes and improvements to the 2.x series: it makes difference between

branches smaller, which in turn makes merging up from 2.x to 3.x easier, but also lets the users benefit from those fixes and improvements earlier.

Usually, what I do is pick a class or namespace, apply Rector on it, then review the changes. If I spot phpdoc that is wrong, I fix that on the patch branch (currently 2.13.x). If I spot phpdoc that is correct but a bit vague, I make it more precise on the minor branch (currently 2.14.x). After the PR is merged, I merge 2.13.x up into 2.14.x, and 2.14.x up in 3.0.x, and I try running Rector again, this time with correct phpdoc.

That migration is a good use case for the git subcommand I want to introduce to you today, because I need to change branches often. It’s already not unusal to have to do so when maintaining a library, but it’s exacerbated here. Sorry for the Tom Jones earworm.

In this particular case, here is the problem I am facing: imagine you have 10 fixes or improvements to backport from one branch to the others, and that you discover them progressively. How would you proceed? Would you stash changes, switch branches, run composer update for good measure, make your change, commit, then switch back every time? Or would you maybe try to remember several things you need to do, and try to do them all at once? Either solution sounds pretty bad.

The subcommand that can save you from this is git worktree.

It allows you to have ✨several✨ worktrees at once for a single repository.

Creating a throwaway worktree with branch 2.14.x can be done like so:

$ git worktree add /tmp/throwaway 2.14.xThe operation is instant, and in the case of doctrine/orm, there are only 2 steps to be ready to work on that new branch:

$ cd /tmp/throwaway

$ composer updateBut I do not want to create throwaway worktrees… I find the idea of having permanent worktrees very appealing: they are like starting points for new branches I want to create. Each one has its own vendor directory, with the right dependencies.

Also, I prefer to have them neatly grouped in a single directory. I could have a normal repository, and then add worktrees inside, but then git would consider the worktrees themselves as new directories that need to be put under version control. To avoid having that main worktree, you can use a bare repository:

$ git clone --bare git@github.com:doctrine/orm.git doctrine-orm.gitYou will end up with a directory called doctrine-orm.git, and the contents of that directory will be what you usually find in the .git directory If you use git log, you will see the history of the default branch, which the current HEAD points to (2.13.x in our case).

Doctrine uses a consistent branching model on all of its repositories:

- 🐛 bugfixes go to the patch branch;

- 💡 new features, deprecations, improvement go to the minor branch;

- 💥 breaking changes go to the major branch.

At first, I named directories after branches, but when 2.12.x went unmaintained, I no longer had a use for the corresponding directory, and realized I should have one directory per branch type instead. Here is how to create that workforest 🌳🌳🌳:

mkdir ../doctrine-orm

git worktree add ../doctrine-orm/patch 2.13.x

git worktree add ../doctrine-orm/minor 2.14.x

git worktree add ../doctrine-orm/major 3.0.xAfter that, you should end up with something like this

doctrine-orm

├── major # a full 3.0.x doctrine/orm is inside 💥

├── minor # a full 2.14.x doctrine/orm is inside 💡

└── patch # a full 2.13.x doctrine/orm is inside 🐛

doctrine-orm.git # Looks just like a regular .git directory

├── config

├── HEAD

├── hooks

├── objects

├── packed-refs

├── refs

└── worktrees # contains administrative files for your worktreesNote that I could have created the worktrees directly inside doctrine-orm.git, but I don’t want to, I find that messy.

When inside doctrine-orm/*, git still knows where the repository is stored thanks to a .git file in each worktree. Yes, in this case it’s just a one-line file, with a pointer to a directory that holds administrative data for that worktree.

$ cat .git

gitdir: /path/to/doctrine-orm.git/worktrees/minorWhen trying this at first, it broke custom git hooks I had. That’s because when using worktrees, Git will store the administrative data that is common to all three worktrees in the usual directory, but will put worktree-specific administrative data in another directory (here: /path/to/doctrine-orm.git/worktrees/minor). Making the distinction between the git directory specific to a worktree and the git directory shared by all worktrees helped me fix my hooks. It is possible to figure them out from inside a worktree:

$ git rev-parse --git-dir

/path/to/doctrine-orm.git/worktrees/major

$ git rev-parse --git-common-dir

/path/to/doctrine-orm.gitWhen directly inside doctrine-orm, nothing special happens, and you will get the usual error message when trying to issue a git command.

$ git status

fatal: not a git repository (or any parent up to mount point /)

Stopping at filesystem boundary (GIT_DISCOVERY_ACROSS_FILESYSTEM not set).When inside a worktree, you can know the status of all worktrees:

$ git worktree list

/path/to/dev/doctrine-orm.git (bare)

/path/to/dev/doctrine-orm/major e9f3a43f3 [php8-migration-persisters]

/path/to/dev/doctrine-orm/minor cc9e456ed [10238--lockMode]

/path/to/dev/doctrine-orm/patch 28cb24b3c [psalm-5-fixes]What does this unlock?

- Switching branches becomes as easy as switching directories. No need to commit or stash anything.

- I do not need to run

composer updateall the time when switching from one worktree to another. - If I want to, I can even compare and edit the same file on two different branches at once. 🤯

I like that git has such hidden gems, like git worktree or git bisect, that are little known and rarely needed, but are still killer features when you do need them.